“Glass of Château Bolton anyone? Or maybe a nice Easby? Prefer red? We get ours from the Welsh Valleys. Some of the best growers from Bordeaux moved there in the ‘40s so we think they know what they’re doing”.

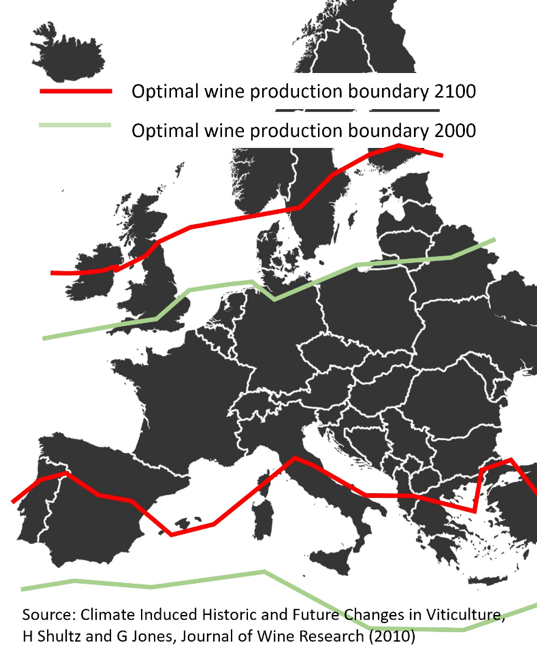

This is by no means a fanciful conversation from the year 2100. According to the Journal of Wine Research, the suitable climate for wine growing is moving towards the poles at quite a rate. A close look at the map above shows the northern limit for wine production in 2100 roughly along the England-Scotland border, by which time southern Spain and Italy may already have become too hot to produce a quality vintage.

Putting aside the crystal decanter for a moment, climate change is causing problems for wine producers already. The established wisdom of generations is in disarray, harvesting is taking place earlier, optimum picking windows are getting shorter and higher peak temperatures are affecting the sugar and acid levels in the grapes, changing the flavour and consistency of the wine they become. The same trends that are improving the quality of Sussex champers are causing sober headaches for Mediterranean producers.

It’s not just quality that is being affected; quantity is suffering too. This year a warm March got the vines budding early, only to find that frosty April wiped them out, so much so that some regions lost 90% of their crop. This has been (according to the French agriculture minister) ‘probably the greatest agricultural catastrophe of the 21st century’. The lack of winter frosts means that pests are surviving in greater numbers and heatwaves and heavy rain are becoming an increasingly worrying reality.

What insurance giant Zurich describes as ‘Wine’s uncertain future’ has already triggered migration, with Australian growers moving to southern Tasmania for a better climate. Others are looking at changing the grapes they grow, with some German producers switching colours and replacing Riesling with Pinot Noir. Historically, Europe has enjoyed a more equitable climate than North America, thanks to its East-West mountain ranges restricting air flows. Consequently, American varieties that can cope with greater temperature variation may replace treasured but more delicate traditional European varieties in the vineyards of France and Italy.

Whatever happens, wine is on the move – literally. “Who’d have thought fifty year from now we’ll all be sittin’ here drinking Côte du Swale”, as a Yorkshireman might say.

Further reading:

https://www.zurich.com/en/media/magazine/2021/how-does-climate-change-affect-wine